Black Lives Matter.

This year cast a renewed light on the injustices the Black community faces every day in America. As the Black Lives Matter movement intensified over the past summer, I felt it was important for my company, Clean Sheet Co., to support it.

Since we make soccer-inspired apparel, and American soccer is a microcosm of our diverse society, my first thought was to create a BLM soccer jersey. We’ve long advocated for the idea of “People’s” jerseys; meaningful alternative designs made directly for fans and supporters instead of officially licensed team gear. Black Lives Matter–a ground-up, people-driven movement–seemed like a perfect fit for this concept. It seemed straightforward: we’d design a soccer jersey in solidarity with Black Lives Matter, release it, and designate proceeds to benefit an appropriate cause.

I readied a few ideas… but something didn’t feel right. It boiled down to this: I’m responsible for Clean Sheet Co., and I’m a white guy. Though I liked what I’d designed, I didn’t trust my perspective. Was I misjudging how best to help? Was I jumping in without invitation, or putting something tone deaf into the world? I believed my intentions were good, but I wasn’t sure I knew how to truly contribute something meaningful to the BLM conversation.

I sought advice from other voices in the community. Based on those conversations, it became clear that anything Clean Sheet Co. produced needed to grow from context and understanding. Instead of moving ahead, I pressed pause. After some time letting things rest, I dove in again in the autumn–not into design, but into research. The goal was to educate myself and to understand more about the entire Black experience in America. I had faith that meaningful visual inspiration would follow.

I began by identifying important eras in Black American history: the West African origin story; the struggle to survive slavery; the bittersweet optimism of emancipation; the blossoming of a new Black American culture in the twentieth century, and the fight for civil rights and enduring justice that leads to our present moment.

Every era, every stitch of Black American history contains multitudes of cultural touchstones: patterns, fabrics, paintings, objects, moments, sounds, symbols. Some, I was familiar with. Many others, I learned about for the first time.

Those touchstones became my inspiration. I picked several, and from them created building blocks: visual swatches. In a way that echoed Clean Sheet Co.’s World Cup 2018 Ribbon Project, I tried to distill these touchstone into repeating patterns. My hope was that after creating these separate pattern swatches, I could combine them into a patchwork that held meaning greater than the sum of its parts. From that patchwork, I could build a jersey–or anything.

I don’t know if I’ve gotten it right, but I want to talk about what I’ve designed, and how it originated. Our BLM concept starts with six unique swatches, corresponding roughly to the chronological eras mentioned above.

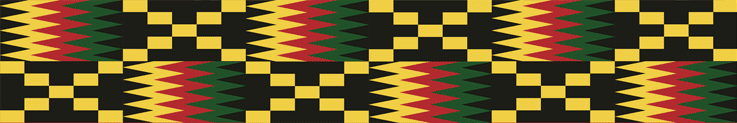

Swatch 1: Inspired by a West African Asante Kente pattern

The Black American experience begins in West Africa. Ghana, on the continent’s so-called Slave Coast, saw millions of its citizens captured and sold into slavery in the Americas.

Amongst the African textile traditions, Ghanaian Kente patterns stand out for their geometric intricacy. The Asante variant is traditionally made for, and worn by, royalty; its patterns evoke strength, ceremony and legacy.

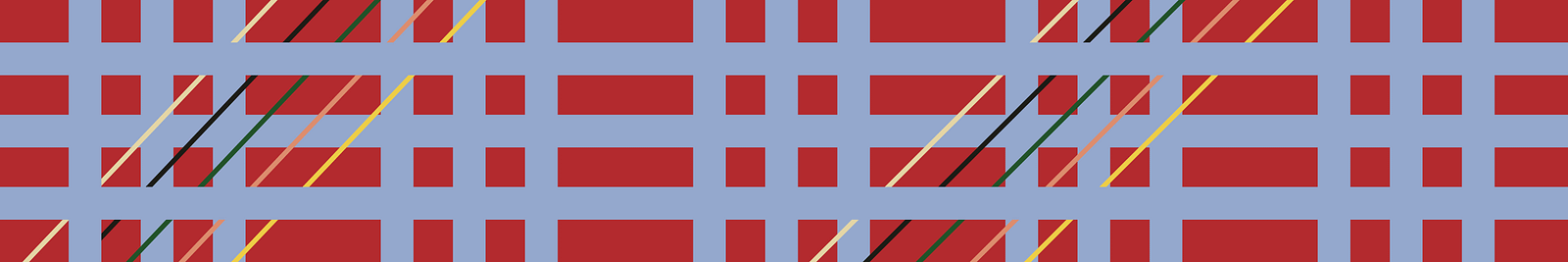

Swatch 2: Inspired by a dyed “Slave Cloth” textile

from the 18th century period of American slavery

During the darkest days of slavery, Black Americans found incredible ways to keep cultural and personal expression alive. Slaves often turned bleak realities into expressions of hope.

So-called “slave cloth” was rough, cheap, bland fabric made specifically to clothe enslaved Blacks. It was the antithesis of hope–created particularly to give slaves a dispiriting “uniform” of sorts that was meant to foster a sense of inferiority to their white captors. And yet, hope prevailed:

Working with imperfect tools and methods, slaves found ways to sew, dye and repurpose the plain cloth into beautiful, vibrant textiles. The swatch created for this project is a visual amalgam of several dyed and patterned textiles.

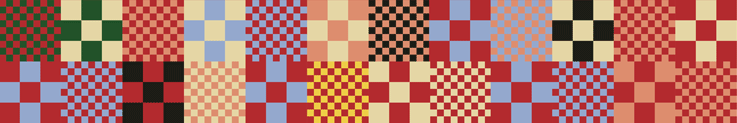

Swatch 3: Inspired by quilted tiles created

by enslaved seamstresses in the mid-19th century

Quilts played a large role in the life of Black American slaves. They were practical, allowed for an incredible range of visual expression, and may have even helped to communicate coded messages along the Underground Railroad.

This swatch takes inspiration from a patchwork quilt designed and created by two seamstresses, Martha and Sarah, who were enslaved in Tennessee during the Civil War period. It is unclear whether the quilt was produced just before, or just after, emancipation.

Swatch 4: Inspired by The Prodigal Son,

a painting by Harlem Renaissance artist Aaron Douglas

As the twentieth century began, Black Americans had been emancipated from slavery for several generations, but faced incredible challenges making progress towards social and civil equality. Jim Crow laws and other forms of systematic racism were enacted to hinder the progress of Black people. The system couldn’t halt the societal gains they were making, but it did harden societal divisions. Within those divisions, vibrant pockets of Black culture flourished.

In these places, like Harlem in the 1920s, incredible artistic and social achievements were woven into a fabric of time and place. This swatch is inspired by the work of a contemporary of that scene, African-American artist Aaron Douglas, who captured the visceral excitement of a Harlem night in 1927.

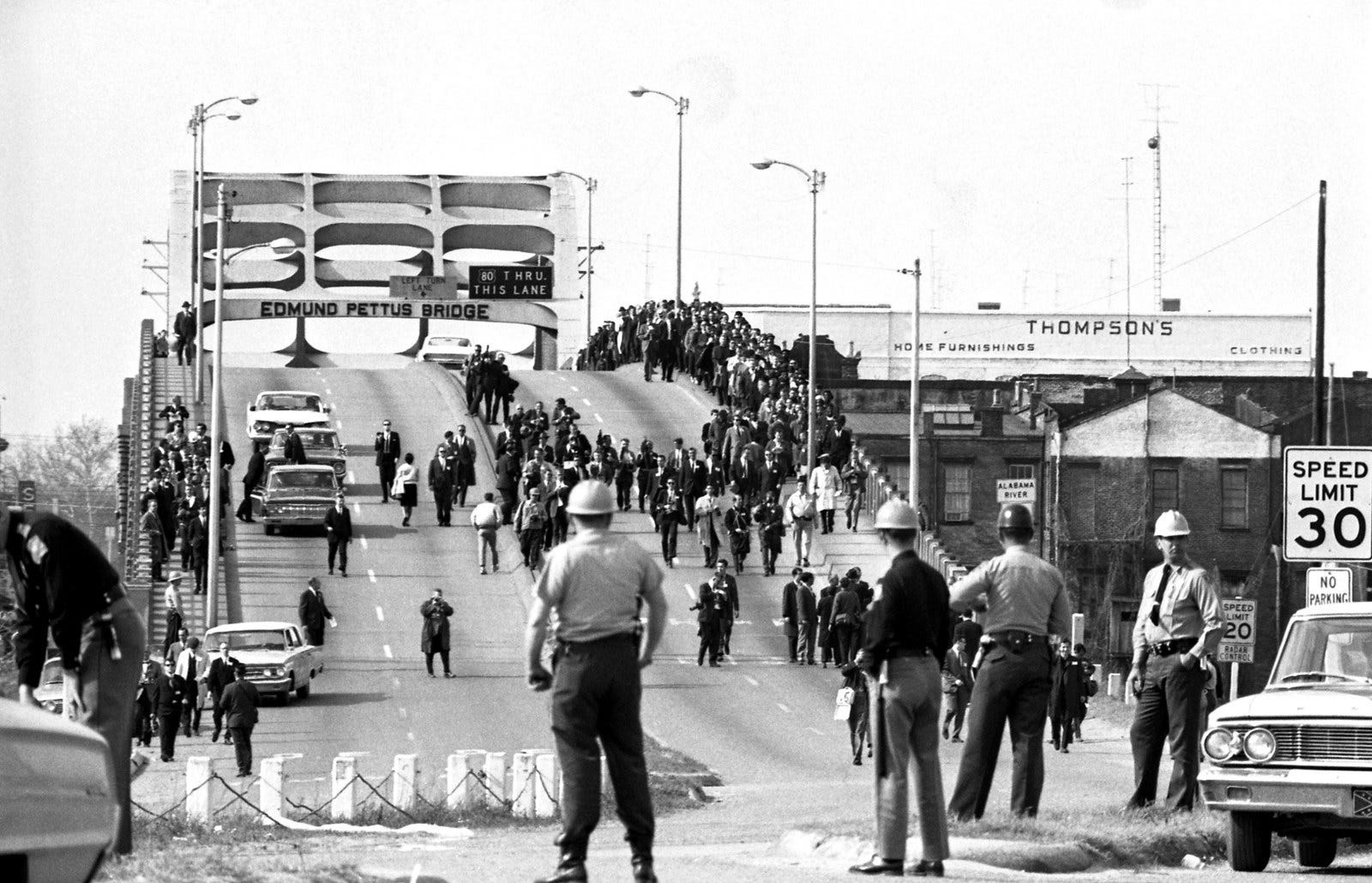

Swatch 5: Inspired by the Edmund Pettus Bridge,

a Civil Rights landmark

In the 1950s and 60s, the Black American experience galvanized around calls for civil justice. In the South, where racial segregation had persisted for a century, a generation of inspirational voices rose to meet the moment. John Lewis was one such figure. A contemporary of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Lewis became an influential leader and a fiery voice for justice in the Black community. In 1965, while leading a peaceful march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, Lewis and marchers were confronted on the Edmund Pettus Bridge by armed police who demanded they disperse.

When they did not, the police took violent action; Lewis escaped with a fractured skull and permanent scars. He went on to work in voting rights organizations, and then to represent Georgia’s 5th congressional district in the U.S. House of Representatives for 37 years. The Pettus Bridge has since become a symbol of Black perseverance and determination, and is now a national historic landmark. During the summer of 2020, as civil rights protests were taking on a new urgency, Lewis passed away–leaving a legacy of progress.

Swatch 6: Inspired by the Black Power raised fist icon,

now synonymous with Black Lives Matter

The Black American experience has, in the early twenty-first century, entered a new chapter. Black Lives Matter is both a rallying cry and a continuation of the Black community’s long struggle for justice and equality. BLM is symbolized most notably by a powerful icon: the raised black fist.

The symbol originated in 20th century revolutionary movements, and became used by the American Black community during the civil rights era, but has come to define the modern BLM coalition. Alternating red and black colors describe the urgency and energy of the movement; in this rendition, the fist is shown just breaking into the vertical frame to project upward momentum.

Together, these six swatches combine to form a square tile that (I believe) has a world of visual potential.

I tried recombining the tile in a few ways, but always came back to a simple opposing-edge woven pattern.

The result, when applied to a jersey, looks like this.

The alternating rotation of the tile creates snaking paths as the swatches connect and lock together in interesting, even unexpected ways. A slight upward tilt suggests (to me) deliberate, positive progress.

I used basic black hem treatments for the arms and neck, and a simple maker’s mark in an effort to not compete with the pattern. I also decided to go without a specific national crest; a USA-inspired symbol just didn’t seem right, and nothing else made sense to me either.

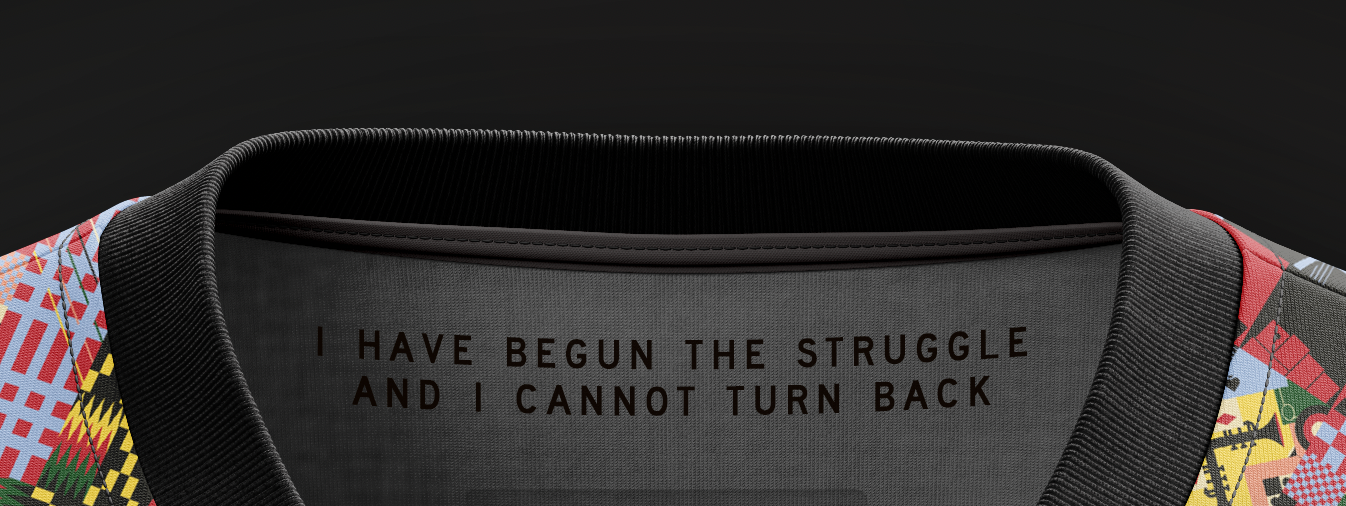

Inside the neck is a quotation from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. that I believe ties the entire project together. “I have begun the struggle, and I cannot turn back.”

This is our BLM concept. It’s been an honor to spend time on this project. We haven’t made anything yet, and I’m not sure we will. At this point, I’d like to hear your thoughts–about the idea, the design, the approach, whether we should make this jersey, worthy causes to support–anything.

In any and every way we can be, Clean Sheet Co. is an ally in this fight. To those on the front lines, and those who support them: you are an inspiration. Black Lives Matter.